|

|

|

Overview of the Yōkai Database |

|

The International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) has conducted joint

research projects on mysterious phenomena and yōkai [1], hosting symposia and workshops that theorize and

historicize these topics with researchers from East Asia and anglophone countries [2].

Building on these efforts, we have provided an English-language overview of the database, introducing

key terms such as “yōkai,” “oni,” “demon,” and “god.”

This database aims to comprehensively collect and organize cases related to mysterious phenomena and yōkai,

drawing from folklore studies and related investigations. By making this information accessible in a

searchable format, the database serves both researchers and the general public worldwide.

While the primary search interface is in Japanese, we encourage international users to explore and utilize

this valuable resource.

|

|

|

|

|

Development of the Database |

|

The Yōkai Database was developed by Professor Emeritus Kazuhiko Komatsu, the 6th Director of

Nichibunken and a leading authority in research related to yōkai, in collaboration with Professor Shoji Yamada,

an expert in information science. Professor Komatsu envisioned a system that would enable users to easily

search for and view yōkai-related materials, previously difficult to obtain, from home alongside reliable

bibliographic information.

The database contains records collected nationwide, documenting yōkai and mysterious phenomena through essays,

folklorists’ reports, and oral accounts by ordinary people, spanning from the late Edo period to the present [3].

Works that are widely regarded to be fictional, such as traditional folktales (mukashi banashi), are excluded.

Literature meeting these criteria was collected and digitized through the efforts of the Database Creation

Committee (now the Yōkai Project Office), young researchers, and graduate students.

Launched on June 20, 2002, the database attracted over 100,000 users within its first three days, coinciding

with the growing global popularity of yōkai through manga, anime, video games, and other pop culture.

Over two decades later, as of November 2023, the database comprises 35,257 entries.

|

|

|

|

|

Key Features |

|

The database provides detailed entries for each mysterious phenomenon and yōkai, including

the name, author, reference information, collection area, and a short abstract.

The “Full Text Search” feature enables users to search across all fields for specific terms.

In 2007, two advanced tools were introduced:

- Advanced Search: Allows users to filter results by specific fields.

- Name List: Offers a comprehensive list of yōkai and mysterious phenomena names from across Japan.

For example, searching for “kitsune” (fox) yields 3,300 records. One entry describes a

“kurosawa no sambonashi gitsune” (a three-legged fox in Kurosawa).

Results include detailed bibliographic information such as reference numbers, names or titles,

phonetic readings, authors, publication details, page references, and geographical origins

(e.g., prefectures, cities, districts). Efforts are continually made to update place names in the

database to reflect municipal boundary changes.

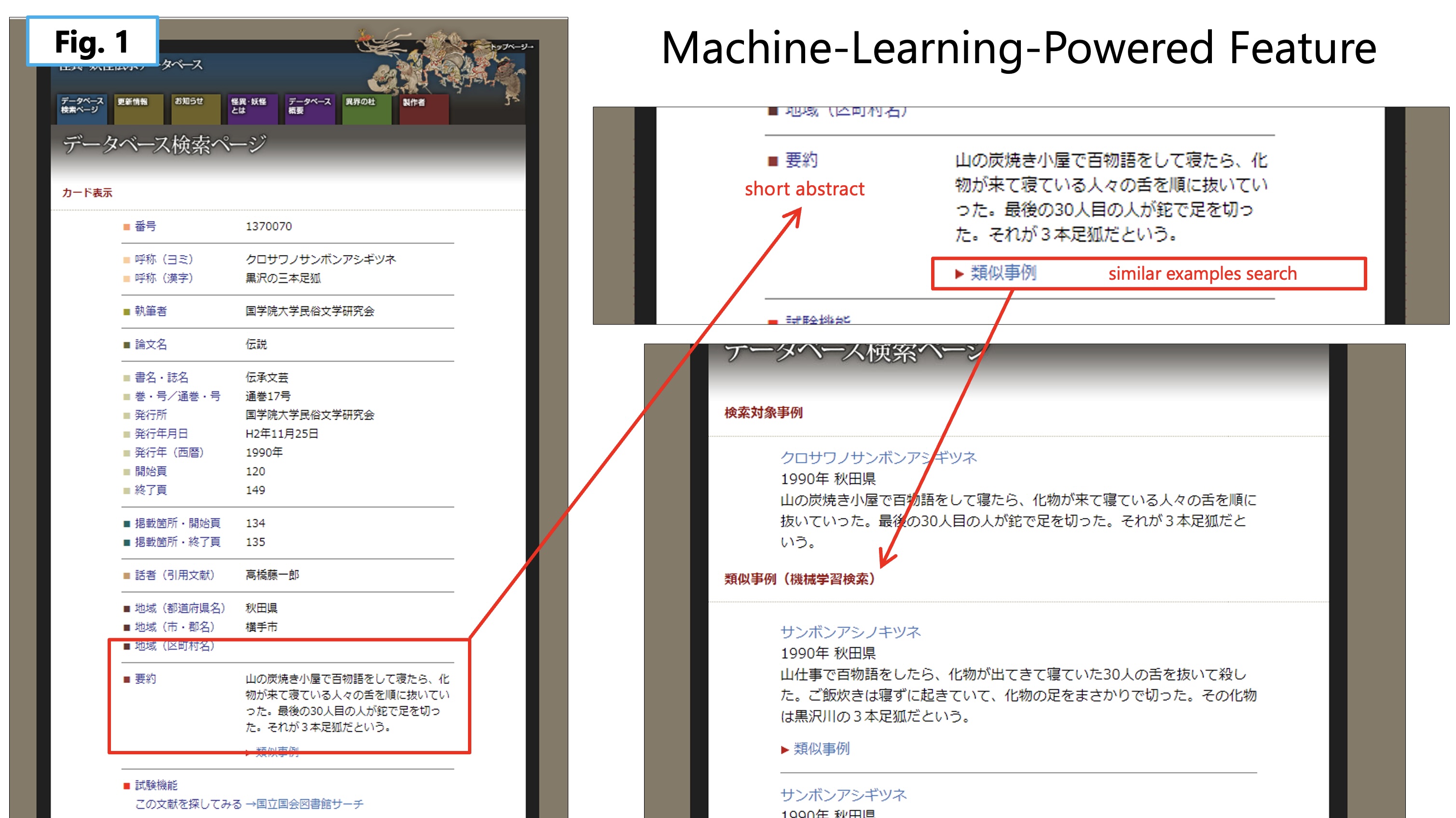

In November 2022, the database introduced a machine-learning-powered feature to search for similar examples

(Fig.1). This innovation enables users to discover unexpected or lesser-known entries, greatly expanding the

scope of research possibilities. In November 2022, the database introduced a machine-learning-powered feature to search for similar examples

(Fig.1). This innovation enables users to discover unexpected or lesser-known entries, greatly expanding the

scope of research possibilities.

|

|

|

|

|

What is Yōkai Culture? |

|

Kazuhiko Komatsu defines yōkai as follows in his book,

An Introduction to Yōkai Culture: Monsters, Ghosts, and Outsiders in Japanese History.

The word yōkai is an ambiguous term among both academics and lay-people. Generally speaking, it means

creatures, presences, or phenomena that could be described as mysterious or eerie.

This is, in my opinion, the broadest definition of yokai. However, what it describes isn’t unique culture.

We can eliminate some ambiguity while retaining this breoad definition by dividing the term’s meaning into

three “domains”: yōkai as incidents or phenomena, yōkai as supernatural entities or presences, and yōkai

as depictions. (p.12)

|

|

|

|

|

Glossary of Important Terms |

|

【yōkai 妖怪】

1. (Chinese derived) (n.) Something of strange appearance with unknowable or mysterious powers. 下學集、太平記. 2. (adj.) strange, mysterious, abnormal. Today the term is used more broadly in popular culture; Michael Foster gives “monster, spirit, goblin, ghost, demon, phantom, specter, fantastic being, lower-order deity, or, more amorphously, as any unexplainable experience or numinous occurrence” (Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese monsters and the culture of yōkai, 2009, University of California Press, p. 2.).

【kaii 怪異】

(“supernatural,” “strange,” “mysterious,” “supernormal,” “anomalous,” “extraordinary” phenomenon or experience.)

Less satisfactory English terms are “uncanny” (Freud) and “fantastic” (Todorov). Zhiguai (J. shikai) 志怪,

a foundational genre (up through Six Dynasties), is often translated as “accounts of the strange.”

In premodern Japan, “anomalies” occur because of cosmic unbalance or societal disorder, which were considered

omens (zenchō 前兆), warnings, or punishment.

Robert Campany uses the term “anomaly accounts” or “record of anomalies” to describe a wide range of texts such

as Soushenji 捜神記 (J. Sosenji) by Gan Bao (ca. 335-349).

【kami 神、カミ】

(“superhuman being,” “elevated spirit,” “divinity,” “god,” “lower-order deity,” “family deity,” “shrine god”).

Many different kinds of kami exist, and humans, plants, animals, and mountains can become kami. 1)

personified kami in Japanese myths, 2) kami worshipped at shrines, 3) kami that come and go like the yama-no-kami

(god of the mountain), 4) small or lower-level kami who reside in plants, trees, animals (such as inari, the fox

god), 5) emperor as living kami, 6) ancestors, family deities, or the “venerated ones” (senzo), 7) and kaminari

(lightning-thunder).

【oni 鬼 (also read ki) 】

(“daemon,” “demon,” “ogre,” “devil,” “spirit of the dead,” “plague god”).

The range of oni is as wide and as diverse as kami. Usually male.

Oni are not necessarily evil and can become a kami if worshipped (as Komatsu Kazuhiko argues).

Often hidden or invisible (one dictionary uses the graph 隠, “to hide”).

Major types of oni include: 1) “ghosts,” “spirits of the dead” (Chinese meaning), 2) “invisible beings,” and

3) “superhuman evil beings.” Buddhist associations include: 1) “hungry ghosts” (gaki 餓鬼), 2) “fiends”

(yasha 夜叉, Skt. yakusa) who harm people and buddhas, 3) “demon-gods” (kijin 鬼神) that protect the buddha and

people, 4) “hell wardens” (gokusotsu 獄卒) who assist King Enma and who have ox or horse heads (gozumezu 牛頭馬頭).

In onmyōdō (Yin-Yang Belief), oni is a god that brings plague (yakujin 厄神).

In annual observances such as tsuina 追儺, “driving out the demon,” or setsubun, oni are chased away.

【yūrei 幽霊】

(“ghost,” “wandering spirit,” “restless spirit,” “lost soul,” “disembodied soul,” “specter,” “phantom,” “apparition”).

The term yūrei was not used widely until the Muromachi period (15th c.), in noh theater, where it frequently

appears to mean spirits of the dead that linger or seek liberation (jōbutsu).

The term “revenant” seems, inappropriate since it implies the resurrection of a corpse.

|

|

This glossary comes from “Issues in Translating Key Japanese Terms,” both in English and

Japanese in “Questioning the ‘Supernatural’ in Chinese and Japanese Literature/Culture” by Haruo Shirane,

Professor at Columbia University, in Yōkai in the Global Context (グローバル時代を生きる妖怪)

edited by Manami Yasui (Serica Shobō, 2025).

In his glossary, there are many important words regarding mysterious phenomena and yōkai explained,

so please refer them.

March 2025

Manami Yasui Ph.D. and Shoji Yamada Ph.D.

Yōkai Project Office, International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

|

|

|

|

|

References |

|

Komatsu, Kazuhiko, 2017, An introduction to yōkai culture :

monsters, ghosts, and outsiders in Japanese history; translated by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, 2017,

Tokyo: Japan, Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (English translation of: 妖怪文化入門,

originally published: Tokyo: Kadokawa Gakugei Shuppan, 2012).

Michael Dylan Foster, 2009, Pandemonium and parade: Japanese monsters and the culture of yōkai,

Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes |

|

[1] Nichibunken Joint research projects; Principal Investigator: Komatsu, Kazuhiko;

1. “Interdisciplinary Research on the Formation and Evolution of Kaii and Kaidan Culture in Japan” (1997.10-2002.3),

2. “Traditions and Transformations of Kaii and Yōkai: From Pre-modern to Contemporary Japan” (2006.4-2010.3),

3. “Tradition and Creation of Kaii and Yōkai Culture: Towards Further Development of Research” (2010.4-2014.3).

[2] Visiting the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University, 2024.4.19.

Symposium: Theorizing and Historicizing Yōkai in Global Context at Nichibunken, 2023.12.16.

Symposium: “Perspectives of Nature and Spirits in East Asia: Focusing on Yōkai,” 2024.10.18-19.

[3] The bibliographies from which data were collected are: folklore-related journals

(those listed in Minzokugaku kankei zasshi bunken sōran, the Bibliography of Folklore Journals,

edited by Takeda Akira, 1978), Nihon zuihitsu taisei, Collection of early modern and modern essays (1975-78),

folklore editions of history books compiled in each prefecture and “Yōkai meii” by Yanagita Kunio.

|

|

|

|

|

| Copyright (c) 2002- International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan. All rights reserved. |

|